Directed by Anthony Mann

1960

The United States of America

It started, quite literally, with a bang. An estimated 50,000 people listened for that fateful gunshot which signaled the start of the 1889 Oklahoma Land Rush. The rules were simple: at 12:00 noon, two million acres of Oklahoma land became free for the taking. All you had to do was be the first to stake a claim, and 160 acres of prime Oklahoma land was yours for the taking. Of course, you had to be the first to get there. So on that fateful morning, thousands of homesteaders lined up on the Oklahoma border, eager for a new life. Never mind that the land used to belong to the Cherokee and Sioux, there were white families to think about. Among these settlers were Yancey and Sabra Cravat. Little did they know, but their lives would represent the great American struggle of Manifest Destiny in all of its glory and shame. Ahead of them lay adventure and heartbreak, success and strife, glory and tragedy. Theirs’ would be the story of the Old West. Theirs’ would be the story of Cimarron.

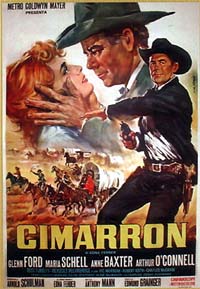

There are two ways to interpret Cimarron. The first is to simply take it at face value. In doing so, you are presented with a Western of staggering scope and complexity. Director Anthony Mann, who had previously revolutionized the Western genre with his work with James Stewart, went about making Cimarron one of the biggest films of his career. In fact, Cimarron was the first of Mann’s three great cinematic epics (the other two being El Cid and The Fall of the Roman Empire). Everything about this film was massive. It featured such big name stars as Glenn Ford, Maria Schell, and Anne Baxter. It sported a tremendous musical score written by two time Academy Award winning composer Franz Waxman. Robert Surtees, the three time Academy Award winning cinematographer (most famous for his work on Ben Hur), manned the cameras. Coming in at a whopping 147 minutes, it looked big, sounded big, and felt like one of the biggest Westerns ever made.

But there is a second way to view Cimarron: as a devastating allegory of American Westward expansion. The film followed the Cravat family as they strove to make their fortune in the untamed wilds of the American West. Yancey is the all-American pioneer: handsome, friendly, popular with everyone he meets. Always looking for the next opportunity. His wife, Sabra, is an immigrant. She is everything that Yancey is not: quiet, emotional, desperate to settle down. But they still desperately love each other. The relationship between Yancey and Sabra represents the duality of the American spirit, one that is restless yet cautious, full of bravado yet thirsty for a sense of security.

But the allegory goes deeper. Sabra is an unabashed racist. She is extremely vocal of her distrust of blacks and Indians. Yancey, on the other hand, crusades for the rights of Indians and other minorities. When an Indian couple tries to take part in the Oklahoma Land Rush and are subsequently lynched, Yancey kills the perpetrators. So, in a sense, Yancey represents the idealistic side of American culture: the idea of the ethnic melting pot, that all men, no matter who they are or where they come from, are equal. Meanwhile Sabra represents the honest truth.

I could wax philosophical about all of the ways that Yancey and Sabra could be interpreted. But really, the story is the most symbolic part of the film. After greedily sucking up all of the Indians’ land via the Land Rush, the settlers force even more land from the Indians. Yancey is desperate to take part in the colonization of the stolen Cherokee land...so much that he literally abandons his wife to pioneer it. Yancey frequently takes long leaves of absence to satisfy his wanderlust: he goes to Alaska and kills a grizzly bear, he takes part in the Spanish-American war, he even travels a good part of the world. He is gone for so long that Sabra has to raise their infant child almost to maturity alone. If Yancey is the spirit of American idealism, then Cimarron bravely explores its sinister side: America’s willingness to abuse and abandon whatever gets in its way, be it the environment, the sovereignty of natives and foreign countries, and even its own citizens. Yancey is both hero and villain. But he does come back in the end. Sabra, much to our surprise, welcomes him home. They may be opposite sides of the American identity, but they can never be separated for very long.

Released in 1960, Cimarron was actually a remake of the 1931 film of the same name which had won three Academy Awards, including Best Picture. The original had been a massive success and was infamous for two things. The first was its depiction of the infamous Oklahoma Land Rush which utilized more than 5,000 extras, 28 cameramen, and an untold army of camera assistants and photographers. Its second claim to fame is additionally the reason why almost nobody has heard of it or seen it since its release in the 1930s: its racist depiction of ethnic minorities. Blacks, Jews, and Native Americans are all represented in this film, but in a poor fashion. The blacks all talk like Stepin Fetchit and the less said about the depiction of Native Americans, the better. Of course, people who have actually seen the original know that the film’s racist depictions of minorities are juxtaposed by Yancey Cravat’s progressive views. But people don’t remember Yancey’s struggle to highlight the unfair results of treaties with the Cherokee Indians. They just remember the smiling black shoeshine who dies in the arms of his massa in one of his first scenes.

But under the watchful eye of director Anthony Mann, the story, and characters, of Cimarron take a drastic change for the better. Yancey and Sabra help run a progressive newspaper that fights for the rights of minorities and exposes the evils of local land barons and criminals. The minorities, in particular the Indians, are portrayed with much more dignity. Yes...this can be seen as an attempt to make the story more politically correct. But in a way, it emboldens the characters and makes them more heroic. Ever since the days of John Ford, the American Western has been one steeped in mythology and allegory...at least until the 70s and 80s with the birth of the Revisionist Western. In a since, by making the film more politically correct, they are honoring the spirit of the American Western.

For whatever reason, Anthony Mann’s Cimarron has fallen into painful obscurity. It is revived every now and then by appearing on television...but it has never been remembered as the great piece of filmmaking that it truly is. Even back during the time of its release, it was largely over-looked. This is a tremendous shame. Cimarron is a part of the grand tradition of American Westerns. Until the time when it finally gets its day in the sun, we shall just have to wait...just like Sabra did for ol’ Yancey...

Good review, I'll have to check this film out when I start watching Westerns.

ReplyDeleteExcellent review, one which made me want to see this. I've owned it for a long time but have yet to watch it. It just moved up to the front of the pile. Very interesting about how the characters represent different sides of America. Looking forward to watching this one. Thank you, sir.

ReplyDeleteRVChris

ReplyDeleteYeah...you need to get around to that, bro!

Kevin Deany

ReplyDeleteGlad to help, my friend! Please...tell me what you think after you watch it!

I've seen the original Cimarron, Nate, but not this one. I'll have to rectify that! You make it sound so exciting, and I'd love to see what differences there are in each movie. Wonderful article!

ReplyDeleteThere are noticable difference. But they're both absolute classics in my humble opinion.

ReplyDelete