Directed by William Peter Blatty

1990

The United States of America

Dammit! It isn’t supposed to work this way! Everyone knows the rules to making Hollywood sequels, particularly for horror films! The first one is supposed to be an instant classic that breaks the rules and challenges preconceived notions about horror (i.e. Jaws, Halloween, Nightmare on Elm Street). Then a half-baked sequel comes out that receives lukewarm to negative reviews from critics and audiences (i.e. Damien: Omen II, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2, The Hills Have Eyes 2). And then, in a last ditch effort to squeeze as much money from the public as possible, an abysmal third film comes out that mocks the franchise, offends the fans, and becomes a massive flop (i.e. Child’s Play 3, Amityville 3, Friday the 13th 3). The Exorcist franchise was following the rules perfectly at the start. The Exorcist (1971) was one of the few horror films in history to be critically acclaimed, ludicrously profitable, and nominated for several Academy Awards. It was followed six years later by Exorcist II: The Heretic, a film that did a decent amount at the box office, yet was universally regarded as one of the worst horror sequels of all time. And then, thirteen years later, it was followed by yet another sequel, The Exorcist III. So, by all rational accounts, The Exorcist III should have been a horrendously horrible film, right? Wrong! Not only is The Exorcist III a fantastic horror film and sequel in its own right, at times it is even better than the original!

I know that last sentence is quite an inflammatory one. But I kid you not. The Exorcist III is hands down one of the best horror films that I have ever seen. Directed by William Peter Blatty, the writer of the novel that The Exorcist was based on and its Academy Award winning screenplay adaption, The Exorcist III both honors and respects the legacy laid down by the first film while looking ahead towards new horizons. Blatty wisely decided to ignore the events of Exorcist II: The Heretic when making this film. So, in a sense, The Exorcist III can be viewed as an official sequel to the original.

The Exorcist III is set fifteen years after the original film. It follows Lieutenant William F. Kinderman (George C. Scott), a grizzled old policeman who should have retired years ago. Recently, there have been a series of gruesome murders in Georgetown. A 12-year-old boy was found with his head cut off by the river after being tortured. A local priest was discovered decapitated in a confessional. Kinderman’s best friend, another priest named Father Dyer, was found dead in a hospital bed, having been paralyzed and drained of all of his blood with a catheter while still alive. What’s worse is that on the wall next to his body, the words “It’s a Wonderfull Life” were written in his blood.

It’s a Wonderful Life was their favorite film. A few days before his murder, Kinderman had gone with Dyer to see it in the theaters. But what’s worse is that all of the murders have something in common: they all fit the description of a notorious serial killer known as “The Gemini Killer.” And The Gemini Killer was captured and put to death in the electric chair fifteen years ago.

The original film worked because it operated on two different levels. The Exorcist was not just a horror film, but an investigative mystery as well. In a sense, it was a kind of priest procedural. Father Damien Karras spent a good portion of the film trying to figure out whether it was an authentic possession. He talked with a psychiatrist, had recordings of the possessed girl’s rantings examined by a linguist, and even faked out the demon by spraying it with regular water while claiming it was Holy Water. The film provided ample room for doubt as to whether or not the possession was real. In an introduction given by director William Friedkin on an anniversary re-release of The Exorcist, he mentioned how people seem to take away whatever they bring to the film. If they believe that there is a God and that good will prevail, they see The Exorcist as a tale of triumph. If they don’t believe in a God and have a pessimistic world view, then they see The Exorcist as a confirmation of their convictions. This is especially curious considering how The Exorcist confirms the existence of the supernatural in the final scenes. The fact that people can watch the little girl’s head spin around 360 degrees and levitate in the air and still believe that it was a hoax speaks to the film’s ability to create doubt.

The Exorcist III operates similarly. For the first hour or so, everything is up in the air. It could be a deranged copycat serial killer or a case of the spirit of The Gemini Killer possessing people so he could carry out his murderous deeds. By following Kinderman, an actual cop, the film focuses even more on the investigative aspect of the storyline. There is more suspicion of foul play, more distrust of the supernatural. Of course, in the last act the supernatural is revealed to be the ultimate culprit. That isn’t a spoiler, by the way. There are supernatural forces at work in this film...but not in the way you’d expect.

Also, The Exorcist III remembers one of the most forgotten rules of the horror industry: we won’t be scared about characters in danger if we don’t care about them in the first place. One of the reasons why horror films are so bad these days is that too often they make their characters completely unlikeable. Yes, yes...we know that most of them will die hideous, gruesome deaths...but after establishing them as horrible people, we start to cheer for the killer. In a true horror film, the hero shouldn’t be the killer, but the people who stand up to them. Films like Poltergeist, Jaws, The Shining, Halloween, and The Exorcist remember this. They spend a large chunk of the film making us genuinely care about the people on the screen. Therefore, when a masked killer comes for them, we don’t want them to die...hence the horror. The Exorcist excelled at this. We came to identify with and emotionally connect with the possessed girl, her mother, and the priests involved in her exorcism. In The Exorcist III, the film takes its time, letting us get to know the characters. We find faults in Kinderman, but we sympathize with them. We watch him go to the movies and dinner with Father Dyer. We see them shoot the breeze and reminisce about old times.

When Kinderman learns of Father Dyer’s death, it is one of the film’s most powerful scenes.

The Exorcist III succeeds because we have an emotional investment in the characters.

But what would a great horror film be like without authentic scares? Thankfully, The Exorcist III has plenty. Another one of the great problems with modern horror is that they are too reliant on jump scares; people jumping out of shadows and loud noises that explode out of nowhere. Both The Exorcist and The Exorcist III create horror through atmosphere. Blatty used noted cinematographer Gerry Fisher to create claustrophobic shots and lighting. The film’s two greatest scenes both involve Kinderman interrogating a man in an insane ward who claims to be possessed by The Gemini Killer. I personally consider them to be two magnum opuses of the horror genre. Watch Fisher’s use of camera angles and shadows.

But more importantly, listen. Listen carefully to how...you know what...never-mind. I’m not going to tell you what to listen for. You’ll notice it. I guarantee you.

The Exorcist III is a true triumph of the horror genre. It deserves to be as respected as the original. It makes me weep that to know that he has only directed two films. The Exorcist III proves that he has a genuine talent and distinct cinematic voice. It frustrates me that I can’t tell you more about this film...but that’s just the way things have to be considering that it’s a horror film. If I say too much, it’ll ruin the suspense. All I can do is beg you all to go out and see this film. You won’t be disappointed...or left unscathed...

Friday, September 23, 2011

Friday, September 16, 2011

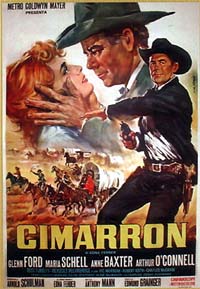

Cimarron

Directed by Anthony Mann

1960

The United States of America

It started, quite literally, with a bang. An estimated 50,000 people listened for that fateful gunshot which signaled the start of the 1889 Oklahoma Land Rush. The rules were simple: at 12:00 noon, two million acres of Oklahoma land became free for the taking. All you had to do was be the first to stake a claim, and 160 acres of prime Oklahoma land was yours for the taking. Of course, you had to be the first to get there. So on that fateful morning, thousands of homesteaders lined up on the Oklahoma border, eager for a new life. Never mind that the land used to belong to the Cherokee and Sioux, there were white families to think about. Among these settlers were Yancey and Sabra Cravat. Little did they know, but their lives would represent the great American struggle of Manifest Destiny in all of its glory and shame. Ahead of them lay adventure and heartbreak, success and strife, glory and tragedy. Theirs’ would be the story of the Old West. Theirs’ would be the story of Cimarron.

There are two ways to interpret Cimarron. The first is to simply take it at face value. In doing so, you are presented with a Western of staggering scope and complexity. Director Anthony Mann, who had previously revolutionized the Western genre with his work with James Stewart, went about making Cimarron one of the biggest films of his career. In fact, Cimarron was the first of Mann’s three great cinematic epics (the other two being El Cid and The Fall of the Roman Empire). Everything about this film was massive. It featured such big name stars as Glenn Ford, Maria Schell, and Anne Baxter. It sported a tremendous musical score written by two time Academy Award winning composer Franz Waxman. Robert Surtees, the three time Academy Award winning cinematographer (most famous for his work on Ben Hur), manned the cameras. Coming in at a whopping 147 minutes, it looked big, sounded big, and felt like one of the biggest Westerns ever made.

But there is a second way to view Cimarron: as a devastating allegory of American Westward expansion. The film followed the Cravat family as they strove to make their fortune in the untamed wilds of the American West. Yancey is the all-American pioneer: handsome, friendly, popular with everyone he meets. Always looking for the next opportunity. His wife, Sabra, is an immigrant. She is everything that Yancey is not: quiet, emotional, desperate to settle down. But they still desperately love each other. The relationship between Yancey and Sabra represents the duality of the American spirit, one that is restless yet cautious, full of bravado yet thirsty for a sense of security.

But the allegory goes deeper. Sabra is an unabashed racist. She is extremely vocal of her distrust of blacks and Indians. Yancey, on the other hand, crusades for the rights of Indians and other minorities. When an Indian couple tries to take part in the Oklahoma Land Rush and are subsequently lynched, Yancey kills the perpetrators. So, in a sense, Yancey represents the idealistic side of American culture: the idea of the ethnic melting pot, that all men, no matter who they are or where they come from, are equal. Meanwhile Sabra represents the honest truth.

I could wax philosophical about all of the ways that Yancey and Sabra could be interpreted. But really, the story is the most symbolic part of the film. After greedily sucking up all of the Indians’ land via the Land Rush, the settlers force even more land from the Indians. Yancey is desperate to take part in the colonization of the stolen Cherokee land...so much that he literally abandons his wife to pioneer it. Yancey frequently takes long leaves of absence to satisfy his wanderlust: he goes to Alaska and kills a grizzly bear, he takes part in the Spanish-American war, he even travels a good part of the world. He is gone for so long that Sabra has to raise their infant child almost to maturity alone. If Yancey is the spirit of American idealism, then Cimarron bravely explores its sinister side: America’s willingness to abuse and abandon whatever gets in its way, be it the environment, the sovereignty of natives and foreign countries, and even its own citizens. Yancey is both hero and villain. But he does come back in the end. Sabra, much to our surprise, welcomes him home. They may be opposite sides of the American identity, but they can never be separated for very long.

Released in 1960, Cimarron was actually a remake of the 1931 film of the same name which had won three Academy Awards, including Best Picture. The original had been a massive success and was infamous for two things. The first was its depiction of the infamous Oklahoma Land Rush which utilized more than 5,000 extras, 28 cameramen, and an untold army of camera assistants and photographers. Its second claim to fame is additionally the reason why almost nobody has heard of it or seen it since its release in the 1930s: its racist depiction of ethnic minorities. Blacks, Jews, and Native Americans are all represented in this film, but in a poor fashion. The blacks all talk like Stepin Fetchit and the less said about the depiction of Native Americans, the better. Of course, people who have actually seen the original know that the film’s racist depictions of minorities are juxtaposed by Yancey Cravat’s progressive views. But people don’t remember Yancey’s struggle to highlight the unfair results of treaties with the Cherokee Indians. They just remember the smiling black shoeshine who dies in the arms of his massa in one of his first scenes.

But under the watchful eye of director Anthony Mann, the story, and characters, of Cimarron take a drastic change for the better. Yancey and Sabra help run a progressive newspaper that fights for the rights of minorities and exposes the evils of local land barons and criminals. The minorities, in particular the Indians, are portrayed with much more dignity. Yes...this can be seen as an attempt to make the story more politically correct. But in a way, it emboldens the characters and makes them more heroic. Ever since the days of John Ford, the American Western has been one steeped in mythology and allegory...at least until the 70s and 80s with the birth of the Revisionist Western. In a since, by making the film more politically correct, they are honoring the spirit of the American Western.

For whatever reason, Anthony Mann’s Cimarron has fallen into painful obscurity. It is revived every now and then by appearing on television...but it has never been remembered as the great piece of filmmaking that it truly is. Even back during the time of its release, it was largely over-looked. This is a tremendous shame. Cimarron is a part of the grand tradition of American Westerns. Until the time when it finally gets its day in the sun, we shall just have to wait...just like Sabra did for ol’ Yancey...

1960

The United States of America

It started, quite literally, with a bang. An estimated 50,000 people listened for that fateful gunshot which signaled the start of the 1889 Oklahoma Land Rush. The rules were simple: at 12:00 noon, two million acres of Oklahoma land became free for the taking. All you had to do was be the first to stake a claim, and 160 acres of prime Oklahoma land was yours for the taking. Of course, you had to be the first to get there. So on that fateful morning, thousands of homesteaders lined up on the Oklahoma border, eager for a new life. Never mind that the land used to belong to the Cherokee and Sioux, there were white families to think about. Among these settlers were Yancey and Sabra Cravat. Little did they know, but their lives would represent the great American struggle of Manifest Destiny in all of its glory and shame. Ahead of them lay adventure and heartbreak, success and strife, glory and tragedy. Theirs’ would be the story of the Old West. Theirs’ would be the story of Cimarron.

There are two ways to interpret Cimarron. The first is to simply take it at face value. In doing so, you are presented with a Western of staggering scope and complexity. Director Anthony Mann, who had previously revolutionized the Western genre with his work with James Stewart, went about making Cimarron one of the biggest films of his career. In fact, Cimarron was the first of Mann’s three great cinematic epics (the other two being El Cid and The Fall of the Roman Empire). Everything about this film was massive. It featured such big name stars as Glenn Ford, Maria Schell, and Anne Baxter. It sported a tremendous musical score written by two time Academy Award winning composer Franz Waxman. Robert Surtees, the three time Academy Award winning cinematographer (most famous for his work on Ben Hur), manned the cameras. Coming in at a whopping 147 minutes, it looked big, sounded big, and felt like one of the biggest Westerns ever made.

But there is a second way to view Cimarron: as a devastating allegory of American Westward expansion. The film followed the Cravat family as they strove to make their fortune in the untamed wilds of the American West. Yancey is the all-American pioneer: handsome, friendly, popular with everyone he meets. Always looking for the next opportunity. His wife, Sabra, is an immigrant. She is everything that Yancey is not: quiet, emotional, desperate to settle down. But they still desperately love each other. The relationship between Yancey and Sabra represents the duality of the American spirit, one that is restless yet cautious, full of bravado yet thirsty for a sense of security.

But the allegory goes deeper. Sabra is an unabashed racist. She is extremely vocal of her distrust of blacks and Indians. Yancey, on the other hand, crusades for the rights of Indians and other minorities. When an Indian couple tries to take part in the Oklahoma Land Rush and are subsequently lynched, Yancey kills the perpetrators. So, in a sense, Yancey represents the idealistic side of American culture: the idea of the ethnic melting pot, that all men, no matter who they are or where they come from, are equal. Meanwhile Sabra represents the honest truth.

I could wax philosophical about all of the ways that Yancey and Sabra could be interpreted. But really, the story is the most symbolic part of the film. After greedily sucking up all of the Indians’ land via the Land Rush, the settlers force even more land from the Indians. Yancey is desperate to take part in the colonization of the stolen Cherokee land...so much that he literally abandons his wife to pioneer it. Yancey frequently takes long leaves of absence to satisfy his wanderlust: he goes to Alaska and kills a grizzly bear, he takes part in the Spanish-American war, he even travels a good part of the world. He is gone for so long that Sabra has to raise their infant child almost to maturity alone. If Yancey is the spirit of American idealism, then Cimarron bravely explores its sinister side: America’s willingness to abuse and abandon whatever gets in its way, be it the environment, the sovereignty of natives and foreign countries, and even its own citizens. Yancey is both hero and villain. But he does come back in the end. Sabra, much to our surprise, welcomes him home. They may be opposite sides of the American identity, but they can never be separated for very long.

Released in 1960, Cimarron was actually a remake of the 1931 film of the same name which had won three Academy Awards, including Best Picture. The original had been a massive success and was infamous for two things. The first was its depiction of the infamous Oklahoma Land Rush which utilized more than 5,000 extras, 28 cameramen, and an untold army of camera assistants and photographers. Its second claim to fame is additionally the reason why almost nobody has heard of it or seen it since its release in the 1930s: its racist depiction of ethnic minorities. Blacks, Jews, and Native Americans are all represented in this film, but in a poor fashion. The blacks all talk like Stepin Fetchit and the less said about the depiction of Native Americans, the better. Of course, people who have actually seen the original know that the film’s racist depictions of minorities are juxtaposed by Yancey Cravat’s progressive views. But people don’t remember Yancey’s struggle to highlight the unfair results of treaties with the Cherokee Indians. They just remember the smiling black shoeshine who dies in the arms of his massa in one of his first scenes.

But under the watchful eye of director Anthony Mann, the story, and characters, of Cimarron take a drastic change for the better. Yancey and Sabra help run a progressive newspaper that fights for the rights of minorities and exposes the evils of local land barons and criminals. The minorities, in particular the Indians, are portrayed with much more dignity. Yes...this can be seen as an attempt to make the story more politically correct. But in a way, it emboldens the characters and makes them more heroic. Ever since the days of John Ford, the American Western has been one steeped in mythology and allegory...at least until the 70s and 80s with the birth of the Revisionist Western. In a since, by making the film more politically correct, they are honoring the spirit of the American Western.

For whatever reason, Anthony Mann’s Cimarron has fallen into painful obscurity. It is revived every now and then by appearing on television...but it has never been remembered as the great piece of filmmaking that it truly is. Even back during the time of its release, it was largely over-looked. This is a tremendous shame. Cimarron is a part of the grand tradition of American Westerns. Until the time when it finally gets its day in the sun, we shall just have to wait...just like Sabra did for ol’ Yancey...

Sunday, September 4, 2011

Update: No Review This Week + Storytime

Alas, my dear readers, I cannot do a review this week. I'm still busy getting settled into my new life at New York University Tisch.

But I don't want to leave you all empty handed two weeks in a row. So...I have a story to share.

This is a TRUE STORY.

I live in a suite right on the corner of Washington Square in New York City. As such, I have a roommate. This roommate is a young computer programmer from Southern China. I won't mention his name because he hasn't given me permission to do so online. Anyhow, for the last few days, I've been trying to establish some common ground with my new roommate. However, due to the language barrier, this has been difficult.

But tonight I made a breakthrough.

It turns out that he loves movies, too. He discovered this blog when he was researching me after we were assigned the same room. He remarked that he was astonished that I had written about Jiang Wen's film Devils on the Doorstep. He was amazed because that film is banned in China.

He asked me how I saw the film. I answered that I had seen it on Netflix. He had never heard of the site and wanted to know what it was. I showed him the site, explained how it was basically a giant movie library. He was astonished. Many of the films on Netflix are still banned in China.

For those of you who don't know, China has INSANE restrictions on foreign films shown inside their borders. Incredibly, only TWENTY foreign films are allowed to be shown in China each year. Think about that for a second. The average American probably sees twenty or so films a year at the movie theater. Even then, that's only a fraction of a fraction of a fraction of the number of movies that come out in the US alone. Not only are foreign films nearly impossible to get a hold of in China, many films are outright banned by the government. These banned films include, I kid you not:

-A.I. - Artificial Intelligence

-Avatar

-Back to the Future

-Ben-Hur

-Brokeback Mountain

-The Dark Knight

-The Departed

-Memoirs of a Geisha

-Pirates of the Caribbean: At World's End

-And many, many other Chinese films that have fallen out of favor with the government

And yet, right before my roommate's eyes, I was showing him a site where he could watch all of these films. Even more incredible to my roommate was that this was legal. He asked me if you got in trouble for watching these films. I told him the truth. "No, it's perfectly legal." My roommate was amazed. He told me that in China if you wanted to watch something non-approved by the government, you had to download it. And in China, with their massive agencies designed to keep a close eye on their citizens' internet activities, doing so could get oneself into serious trouble with the law. So naturally he was suspicious and wary of a site with so many banned films.

Then he asked me a strange question: "Don't they ban films in America?" I paused for a second. I wondered what I should say. Then I decided, once again, on telling the truth. "Not really. The federal government can't officially ban a film in this country. Some local governments can, but I can't think of any instances when a movie has been banned by federal law."

Upon hearing my answer, my roommate lowered his head, dropped his eyes to the ground, and said in a half whisper, "That's because America is a free country."

As I write this, my roommate is busy setting up his own Netflix account. I have provided him with a list of great films that I thought that he might enjoy and may never get to see in China. This was one of the first times in my life that I understood just how powerful and meaningful my country's freedoms are. Folks, I'm proud to be an American. I'm proud to live in a country where men and women have given their lives in order to protect my Freedom of Speech. It might sound cheesy, but I really do. And, of course, I recognize the brave men and women who have also given their lives to protect basic human rights in other countries. In the Western world, it's so easy to take our freedoms for granted.

So be thankful, folks. Be thankful that we live in a part of the world where information is free for the taking. For there are many, many people, just like my roommate, who live in places where it is not.

Editor-in-Chief

Nathanael Hood

But I don't want to leave you all empty handed two weeks in a row. So...I have a story to share.

This is a TRUE STORY.

I live in a suite right on the corner of Washington Square in New York City. As such, I have a roommate. This roommate is a young computer programmer from Southern China. I won't mention his name because he hasn't given me permission to do so online. Anyhow, for the last few days, I've been trying to establish some common ground with my new roommate. However, due to the language barrier, this has been difficult.

But tonight I made a breakthrough.

It turns out that he loves movies, too. He discovered this blog when he was researching me after we were assigned the same room. He remarked that he was astonished that I had written about Jiang Wen's film Devils on the Doorstep. He was amazed because that film is banned in China.

He asked me how I saw the film. I answered that I had seen it on Netflix. He had never heard of the site and wanted to know what it was. I showed him the site, explained how it was basically a giant movie library. He was astonished. Many of the films on Netflix are still banned in China.

For those of you who don't know, China has INSANE restrictions on foreign films shown inside their borders. Incredibly, only TWENTY foreign films are allowed to be shown in China each year. Think about that for a second. The average American probably sees twenty or so films a year at the movie theater. Even then, that's only a fraction of a fraction of a fraction of the number of movies that come out in the US alone. Not only are foreign films nearly impossible to get a hold of in China, many films are outright banned by the government. These banned films include, I kid you not:

-A.I. - Artificial Intelligence

-Avatar

-Back to the Future

-Ben-Hur

-Brokeback Mountain

-The Dark Knight

-The Departed

-Memoirs of a Geisha

-Pirates of the Caribbean: At World's End

-And many, many other Chinese films that have fallen out of favor with the government

And yet, right before my roommate's eyes, I was showing him a site where he could watch all of these films. Even more incredible to my roommate was that this was legal. He asked me if you got in trouble for watching these films. I told him the truth. "No, it's perfectly legal." My roommate was amazed. He told me that in China if you wanted to watch something non-approved by the government, you had to download it. And in China, with their massive agencies designed to keep a close eye on their citizens' internet activities, doing so could get oneself into serious trouble with the law. So naturally he was suspicious and wary of a site with so many banned films.

Then he asked me a strange question: "Don't they ban films in America?" I paused for a second. I wondered what I should say. Then I decided, once again, on telling the truth. "Not really. The federal government can't officially ban a film in this country. Some local governments can, but I can't think of any instances when a movie has been banned by federal law."

Upon hearing my answer, my roommate lowered his head, dropped his eyes to the ground, and said in a half whisper, "That's because America is a free country."

As I write this, my roommate is busy setting up his own Netflix account. I have provided him with a list of great films that I thought that he might enjoy and may never get to see in China. This was one of the first times in my life that I understood just how powerful and meaningful my country's freedoms are. Folks, I'm proud to be an American. I'm proud to live in a country where men and women have given their lives in order to protect my Freedom of Speech. It might sound cheesy, but I really do. And, of course, I recognize the brave men and women who have also given their lives to protect basic human rights in other countries. In the Western world, it's so easy to take our freedoms for granted.

So be thankful, folks. Be thankful that we live in a part of the world where information is free for the taking. For there are many, many people, just like my roommate, who live in places where it is not.

Editor-in-Chief

Nathanael Hood